Over my twenty-plus years in technology, I’ve often pondered a critical question: what defines a truly amazing organisation? How do we concoct the “secret sauce” that fosters and maintains high-performing teams? It’s a quest that has led me to revisit one of my all-time favourite reads on organisational and team design, “Team Topologies”. This gem of a book masterfully integrates disparate elements we’re vaguely aware of arounds good organisational and team design into a cohesive narrative, much like Google’s book on Site Reliability Engineering (SRE) did for DevOps.

Reflecting on Google’s notable studies, Project Oxygen and Project Aristotle, conducted in the early 2010s, it’s fascinating how these investigations peeled back the layers on team dynamics. What stood out was the revelation that the secret sauce for team performance hinged less on team composition and more on their overall dynamic. Central to their findings was the concept of psychological safety, allowing team members to experiment, debate, fail, and learn without fear of retribution.

However, as intriguing as these insights are, they beg the question: what does a “safe,” enabled team look like in practice, and how do we cultivate such an environment?

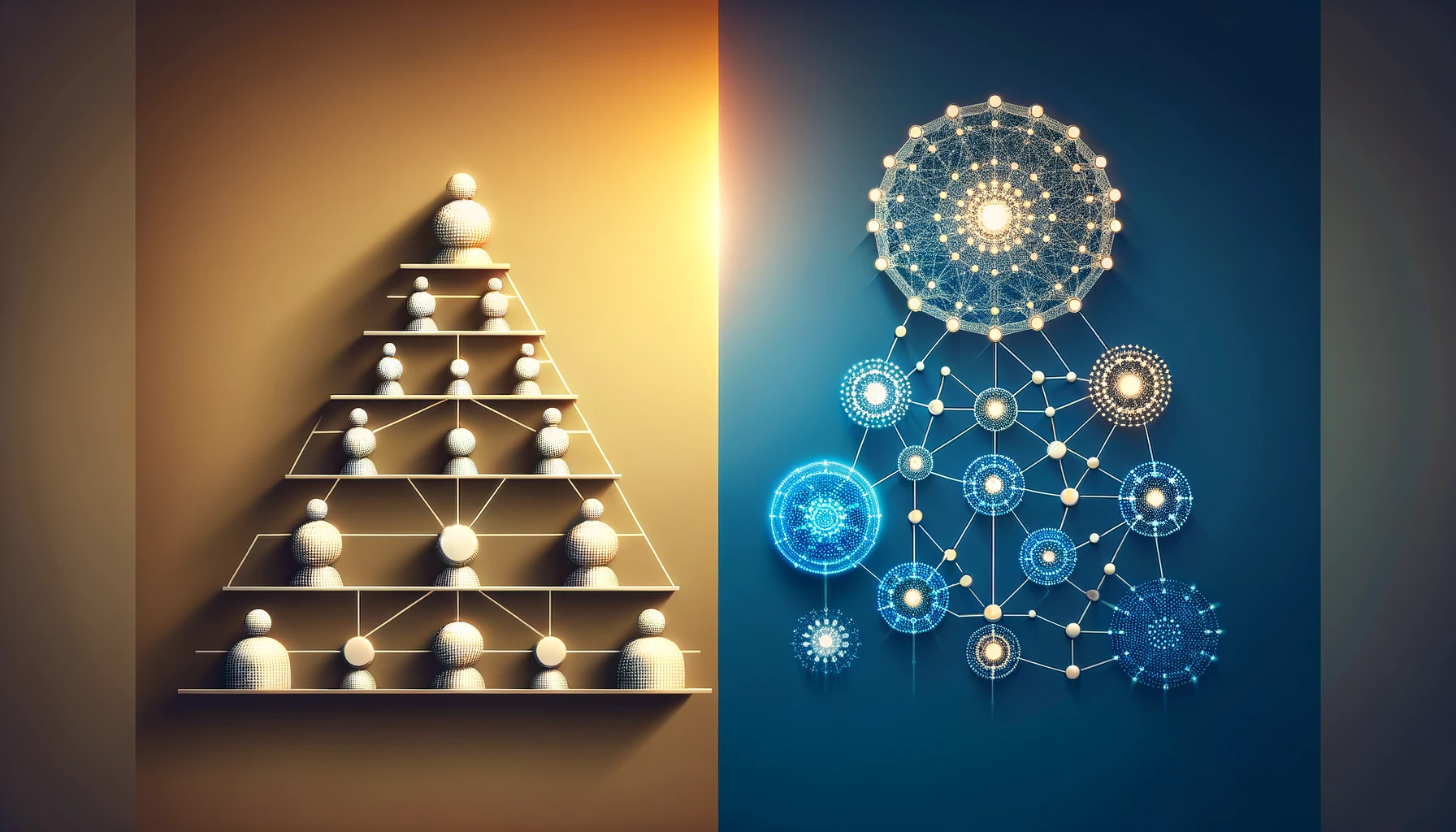

The authors of “Team Topologies” assert that businesses no longer have the luxury of choosing between speed and stability. Large organisations tend to lean toward stability, creating functional silos as a means of exerting control. This outdated mindset overlooks the critical aspect of team enablement, essential for fostering innovative and high-performing teams.

We aim to sculpt enabled, autonomous teams characterised by loose coupling, high cohesion, and clearly defined boundaries of responsibility. This concept echoes the principles of system architecture, where well-designed APIs and integrations provide contracts and understanding between different components.

Before delving deeper, it’s crucial to grasp foundational principles of organisational and team design, and here, Conway’s Law plays a pivotal role. Mel Conway, in his 1967 paper, posited that organisations are doomed—or destined—to create products that mirror their communication structures. This law acts as a homomorphic force, shaping software architecture and team structures in a congruent manner.

Diversity, as highlighted by Tom DeMarco and Timothy Lister in “PeopleWare,” is vital for cultivating cohesive teams. A sprinkle of heterogeneity can significantly boost team gel. When the architecture of systems or designs conflicts, the organizational design prevails, as noted by Ruth Malan.

Understanding Conway’s Law enables us to leverage it as a catalyst for change by designing our architecture to accommodate and even embrace change, as suggested by Don Reinertsen in “Principles of Product Development Flow.”

Yet, while we strive for decoupled organizational and team designs, we must remain mindful of their interaction models. Departments, divisions, and systems can be independently structured, provided their interfaces with the broader organisation are thoughtfully designed.

The goal is to foster long-lived teams that stabilize team dynamics. However, we should avoid static team compositions, as periodic changes are beneficial for realigning and rejuvenating teams.

Now, addressing the critical question of team size: enter Dunbar’s number. Robin Dunbar’s research sheds light on the cognitive limit to the number of individuals with whom one can maintain stable social relationships. These limits—five, fifteen, fifty, and one hundred fifty—offer insights into the natural groupings within organizations.

This understanding aligns with Ken Schwaber’s (the co-creator of Scrum) recommendations for team sizes, 7 plus or mins 2, fitting snugly within the fifteen-person limit for fostering deep trust. Trust and psychological safety are the bedrock of any successful, high-performing team.

Integrating Conway’s Law and Dunbar’s number, we arrive at a “Team-first Architecture” approach, aligning software architecture with the natural dynamics of team sizes and interactions.

As we contemplate team structures or organisational redesigns, these insights can guide us toward more effective, resilient, and fulfilling organisational environments.

In our continuous learning journey, let’s consider these principles not just as theoretical concepts but as practical tools for shaping the future of our organisations.

Yours in learning.

Recent Comments